WikiLeaks books roundup – reviews

Inside WikiLeaks by Daniel Domscheit-Berg; WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange's War on Secrecy by David Leigh and Luke Harding

-

- Inside WikiLeaks: My Time with Julian Assange at the World's Most Dangerous Website

- by Daniel Domscheit-Berg

-

- Buy it from the Guardian bookshop

Of the making of books about WikiLeaks, there is apparently no end. Even as these two dropped on to the doormat, two more turned up on my Kindle. And that's just at the "popular" end of the market. Already one can hear the grinding of academic presses as scholars and essayists set to work, assessing the Meaning Of It All. Never before in the history of mankind (as Churchill might say) has so much trouble been caused by so few people.

The most extraordinary revelation in Daniel Domscheit-Berg's book is how tiny the WikiLeaks operation has been from the beginning. For most of its brief life, it seems to have had a core of only four full-time people with a variable number of part-time supporters, groupies and hangers-on. All in all it's a sobering case study in how mastery of software skills and cryptography can create something capable of infuriating – if not exactly humbling – a superpower.

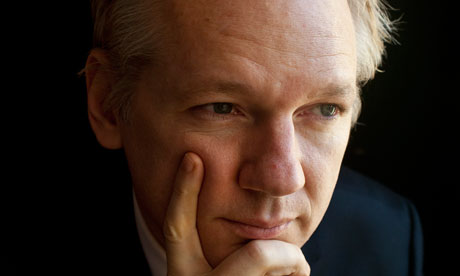

Domscheit-Berg is a computer scientist who worked in IT security prior to devoting himself to WikiLeaks at the end of 2007. He left in September 2010, exhausted and embittered by the stress of working with the site's founder, Julian Assange. His is an intensely personal account of what it was like to be at the epicentre of an internet phenomenon. He portrays himself as a relatively straightforward and idealistic hacker who was mesmerised by a flawed genius, and captivated by that genius's vision of creating a world in which no government or corporation could hide things from the rest of us.

Most of the mainstream media has had a go at profiling Julian Assange, but Domscheit-Berg's portrayal of the WikiLeaks founder is the most insightful to date. Many journalists have commented on his brilliant, wilful, erratic, paranoid personae, but none has lived with him on a day-to-day basis, as Domscheit-Berg did. "Julian often behaved," he writes at one point, "as though he had been raised by wolves rather than by other human beings. Whenever I cooked, the food would not, for instance, end up being shared equally between us. What mattered was who was quicker off the mark. If there were four slices of Spam, he would eat three and leave one for me if I was too slow."

This indifference to the needs of others, together with a maniacal self-centredness and an amazing ability to concentrate on technical problems, is par for the course for computer geniuses. (Think of the portrayal of Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook, in the film The Social Network, or of the early Bill Gates.) It's what enables them to create things, to conjure up unimaginable constructs by sheer force of intellect and will. But it's also what makes them incapable of managing things on a day-to-day basis – and that, in a nutshell, is the burden of Domscheit-Berg's complaint. As he tells it, the task of running and financing a complex operation was difficult enough without having a capricious, secretive and often uncontactable boss who can – and often does – countermand the carefully laid arrangements of subordinates.

David Leigh and Luke Harding have produced an All the President's Men for our times. It tells the story of how the Guardian got involved in some of the biggest revelations in recent journalistic history, and chronicles how the Afghan and Iraq war logs and US diplomatic cables came to be published. It's a rattling page-turner that has Guardian dogs learning lots of new tricks (though they never quite mastered the art of using disposable mobile phones). It also highlights the fact that the paper was probably the best available collaborator for WikiLeaks because it's one of the few journalistic organisations that has taken data journalism seriously and has formidable in-house technical expertise.

One of the lessons of the evolution of WikiLeaks is that the facts rarely speak for themselves. Initially the vision was that all that was needed was to publish information that someone wished to keep secret – that the act of publication was sufficient in itself. What that implied was that WikiLeaks merely needed to construct a secure conduit that would enable whistleblowers to upload stuff without betraying their identities.

Experience showed, however, that often mere revelation was not enough: the world yawned and turned away. Often the leaked material was complex and unintelligible to the lay browser. It needed expert interpretation – and corroboration. So gradually it dawned on Assange and his colleagues that the best way of making an impact on the world might be to collaborate with journalistic organisations, which could provide the interpretation and the checking needed to ensure that people believed what was being leaked. This is the value that the Guardian, the New York Times, Der Spiegel and the other media partners added to the vast troves of documents that Assange brought to them.

But if it turned out that WikiLeaks needed conventional journalism, it has also become clear that conventional journalism needs what WikiLeaks created, namely a secure technology for enabling people to upload confidential material that they believe should be in the public domain. So it's important that serious media organisations now build that kind of technology themselves, just in case WikiLeaks is overcome by the fragility of its finances, its managerial problems or the legal vulnerability of its founder. In a world increasingly dominated by secretive, unaccountable corporations and in which authoritarian regimes continue to flourish, we will need robust technologies for ensuring that some secrets cannot be kept.

The media's obsession with Assange is understandable, for he is indeed an amazingly complex and fascinating individual. It's impossible to read either of these books without being alternately moved and revolted by his behaviour – at least as recounted by those who have had to deal with him. But his significance transcends his personality. Assange unleashed a genie that can't be rebottled. As a result of his work, governments everywhere are faced with a tough choice: to live with a WikiLeakable world or to shut down the net. Not bad for an Australian hacker of no fixed abode.

No comments:

Post a Comment