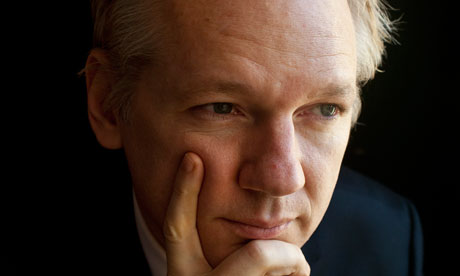

The WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange is to be extradited to Sweden to face allegations of rape and sexual assault. Assange will appeal, his legal team has confirmed. If they lose he will be sent to Sweden in 10 days. Speaking outside Belmarsh magistrates court in south-east London after the judgment, Assange attacked the European arrest warrant system. He dismissed the decision to extradite him as a "rubber-stamping process". He said: "It comes as no surprise but is nevertheless wrong. It comes as the result of a European arrest warrant system amok."

There had been no consideration of the allegations against him, Assange said. His extradition would thrust him into a legal system he did not understand using a language he did not speak. Assange said the US government by its own admission had been waiting to see the British court verdict before determining what action it could take against him.

"What does the US have to do with a Swedish extradition process?" he asked. "Why is it that I am subject, a non-profit free speech activist, to a $360,000 (£223,000) bail? Why is it that I am kept under electronic house arrest when I have not even been charged in any country, when I have never been a fugitive?" Assange had earlier heard the chief magistrate, Howard Riddle, dismiss each of the defence's arguments.

Assange's legal team had contended that the Swedish prosecutor Marianne Ny did not have the authority to issue a European arrest warrant. The magistrate ruled that she did possess this authority and the warrant was valid.

Ny's credibility had been questioned by the defence team but Riddle said those doubts amounted to "very little". A retired judge who had criticised her, Brita Sundberg-Weitman, had no firsthand knowledge or evidence to back up her opinion, he said.

The defence had argued that the allegations against Assange were not offences in English law and therefore not grounds for extradition. But Riddle said the alleged offences against Miss A of sexual assault and molestation met the criteria for extradition, and an allegation made by Miss B if proven "would amount to rape" in this country.

In his summary Riddle accused Assange's Swedish lawyer, Björn Hurtig, of making a deliberate attempt to mislead the court. Assange had clearly attempted to avoid the Swedish justice system before he left the country, Riddle said. "It would be a reasonable assumption from the facts that Mr Assange was deliberately avoiding interrogation before he left Sweden."

The judge was severely critical of Hurtig, who had said in his statement that it was "astonishing" Ny had made no effort to interview his client before he left Sweden. "In fact this is untrue," said Riddle. Hurtig had realised his mistake the night before he gave evidence and corrected his evidence in chief, said the judge. But it had been done in a manner that was "very low key". "Mr Hurtig must have realised the significance of ... his proof when he submitted it," Riddle said. "I do not accept that this was a genuine mistake. It cannot have slipped his mind. The statement was a deliberate attempt to mislead the court."

Riddle acknowledged there had been "considerable adverse publicity against Mr Assange in Sweden", including statements by the prime minister. But if there had been any irregularities in the Swedish system the best place to examine them was in a Swedish trial.

Outside the court Assange's lawyer, Mark Stephens, said the ruling had not come as a surprise and reaffirmed the Assange team's concerns that adhering to the European arrest warrant (EAW) amounted to "tick box justice".

"We are still hopeful that the matter can be resolved in this country," he said. "We remain optimistic of our chances on appeal."

The possibility of a secret trial – which Assange's lawyers argue he could face if extradited – was "anathema to this country and to most civilised countries in the world", Stephens said. During Assange's extradition hearing Clare Montgomery QC, for the Swedish authorities, said trial evidence would be heard in private but the arguments would be made in public. This did not amount to a secret trial.

Stephens suggested Riddle had been "hamstrung" by the EAW. "We're pretty sure the secrecy and the way [the case] has been conducted so far have registered with this judge. He's just hamstrung," he told reporters.

Assange had already paid large amounts to defend himself, with the cost of translating material alone amounting to more than £30,000, Stephens said. "That's a cost the prosecution should be bearing. The prosecution should be translating everything into a language he understands."

Assange has been fighting extradition since he was arrested and bailed in December. He has consistently denied the allegations, made by two women in August last year.

At a two-day hearing this month his legal team argued that Assange would not receive a fair trial in Sweden. They said the EAW issued by Sweden was invalid because the Australian had not been charged with any offence and the alleged assaults were not grounds for extradition.

Assange fears that being taken to Sweden will make it easier for Washington to extradite him to the US on possible charges relating to WikiLeaks's release of the US embassy cables. Sweden would have to ask permission from the UK for any onward extradition. No charges have been laid by the US, though it is investigating the website's activities.

The most serious of the four allegations relates to an accusation that Assange, during a visit to Stockholm in August, had sex with a woman, Miss B, while she was sleeping, without a condom and without her consent. Three counts of sexual assault are alleged by another woman, Miss A. If found guilty of the rape charge he could face up to four years in prison.

Assange will be held in custody because there is no system of bail in Sweden until a possible trial or release.

The Australian ambassador to Sweden, Paul Stephens, wrote to the country's justice minister last week to insist that if extradited, any possible case against Assange must "proceed in accordance with due process and the provisions prescribed under Swedish law, as well as applicable European and international laws, including relevant human rights norms".

European arrest warrants were introduced in 2003 with the aim of making the process swifter and easier between European member states. But campaigners have raised concerns about their application, arguing they are sometimes used before a case is ready to prosecute and have been extended far beyond their original purpose of fighting terrorism. Last year 700 people were extradited from the UK under the system.